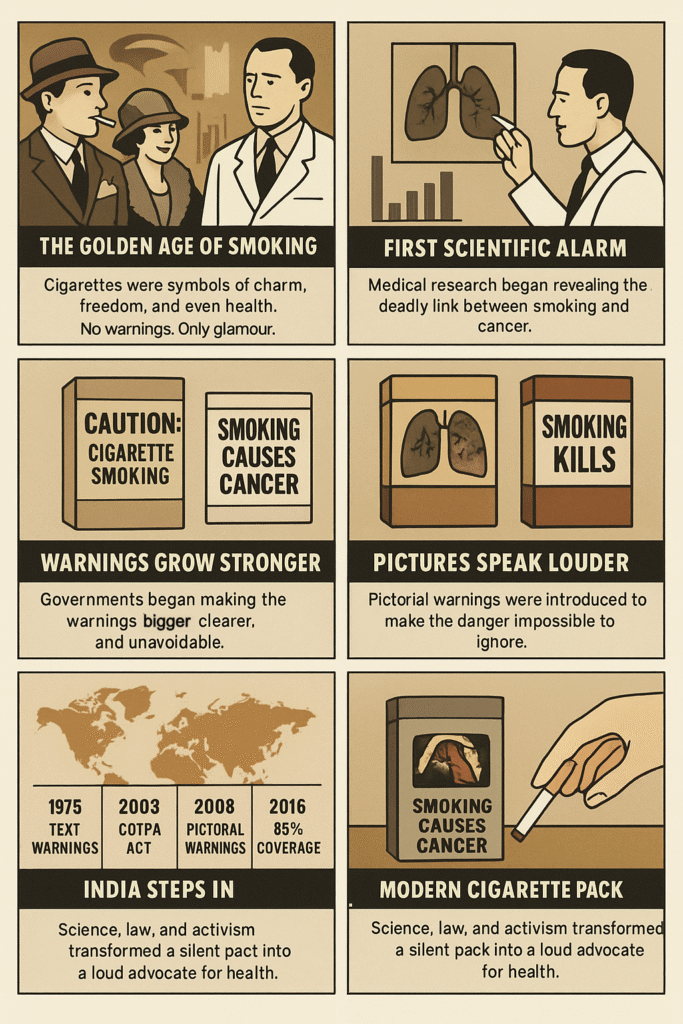

In the mid-1900s, cigarette packs began to change — not their contents, but their conscience. What was once a symbol of style and freedom slowly became a warning label for an entire generation. This blog traces this transformation — from glamour to grim truth — showing how policy, science, and public awareness turned a dangerous habit into a global health crusade. Today, as plastic quietly seeps into our daily lives and our children’s lunchboxes, this story holds a powerful lesson: when evidence speaks, policy must act.

The Age of Glamour

It started in the early 1900s — the “golden age” of smoking.

Cigarettes were symbols of charm, freedom, and even health.

Movie stars puffed on-screen, doctors appeared in ads recommending certain brands, and soldiers got cigarettes in their rations.

No warnings. No guilt. Just glamour.

But quietly, behind the smoke, the first whispers of danger began..

Science Speaks (1940s–1960s)

In the 1940s and ’50s, doctors began to notice something alarming — lung cancer cases were rising rapidly.

In 1950, a groundbreaking paper by Doll and Hill in the British Medical Journal revealed a strong link between smoking and lung cancer.

By the early 1960s, the evidence was undeniable.

Then, in 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Report officially declared smoking a cause of cancer and other deadly diseases.

That was the turning point — when governments realized they couldn’t stay silent anymore.

The First Words on the Pack

In 1966, the United States became the first country to require a health warning on cigarette packs.

It read simply:

“Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health.”

It was small, polite, and easy to ignore — but revolutionary for its time.

Soon, other countries followed, adding their own versions of this quiet honesty.

The Warning Grows Louder

Through the 1970s and ’80s, public health research grew stronger, and so did the warnings.

The text evolved from mild suggestions to blunt truths:

“Smoking Causes Cancer.”

“Smoking Kills.”

The font got bigger. The words got bolder.

And then came another revolution — pictures.

When Words Weren’t Enough

By the late 1990s, the tobacco epidemic had become a global concern.

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) — the world’s first global public health treaty.

One of its key provisions:

Cigarette packages must carry clear, visible, and rotating health warnings — ideally with images showing the effects of smoking.

Canada led the way with graphic pictures of diseased lungs and rotting teeth.

Australia, Brazil, and the UK soon joined in.

The goal was simple — make the pack itself an anti-smoking message.

India’s Turn

In India, the journey was long and hard-fought.

1975: India’s first law, Cigarettes (Regulation of Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, required a basic text warning: “Cigarette smoking is injurious to health.”

2003: The COTPA Act expanded this to all tobacco products, allowing stronger and pictorial warnings.

2008: India introduced its first pictorial warnings — one of the earliest developing nations to do so.

2016: India required that 85% of every pack (front and back) be covered with warnings — making them among the world’s strongest.

Today, every cigarette pack in India declares boldly:

“Smoking causes cancer.”

“Tobacco kills.”

“Quit today.”

The Global Echo

Now, more than 120 countries require pictorial health warnings on tobacco products.

In many, cigarette packs are “plain” — stripped of branding and color, leaving only the warning and manufacturer’s name.

What was once a billboard of glamour is now a poster for public health.

The Moral of the Story

It took science, activism, law, and persistence for the truth to claim its place on every pack.

What began as a quiet line in fine print became a global campaign of honesty — written in bold, often painful imagery.

That’s how cigarette packs, once silent, learned to speak for your lungs.

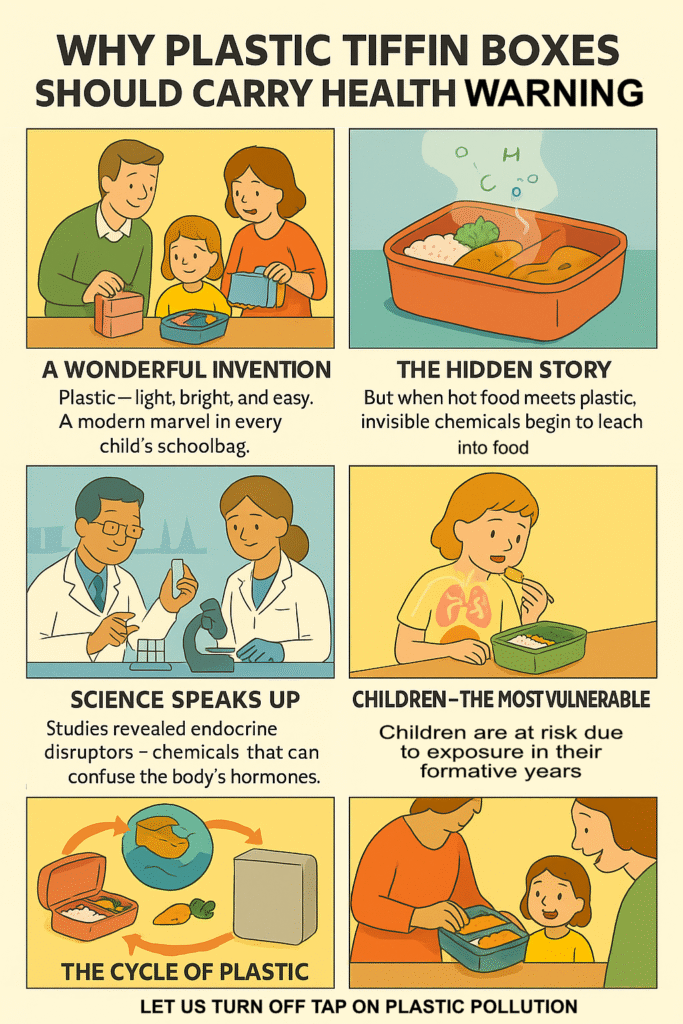

Why Plastic Tiffins Should Carry a Health Warning

1. Plastic Tiffins Are Food-Contact Materials — Yet Poorly Regulated

Plastic containers directly contact food every day — often hot, oily, or acidic food that increases chemical migration. Most tiffins sold in India are made from polypropylene (PP), LDPE, or mixed plastics, and are rarely tested batch-wise for migration limits or chemical additives. Warnings remind parents and schools that “plastic-safe” is not the same as “food-safe.”

2. They Leach Chemicals Linked to Serious Health Risks

When heated or scratched, many plastics release chemicals such as:

- Bisphenol A (BPA) – linked to breast and prostate cancers, early puberty, and diabetes.

- Phthalates – known endocrine disruptors that interfere with hormonal development.

- Styrene, melamine, and additives – can migrate into food under normal use.

Even BPA-free plastics often contain similar substitutes (BPS, BPF) with comparable toxicity.

3. Children Are Especially Vulnerable

- Children eat more food per kilogram of body weight, so exposure per meal is higher.

- Their organs and endocrine systems are still developing.

- Early exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals can cause lifelong health impacts — affecting growth, fertility, immunity, and neurodevelopment.

Warnings serve as a public health nudge for parents and schools to choose safer alternatives.

4. The Problem Continues After Disposal

A tiffin’s story doesn’t end in the lunchbox. When discarded, it degrades into microplastics — contaminating soil, air, and water. These microplastics re-enter the food chain — meaning the same child exposed today through lunch could be exposed again tomorrow through food or water. A life-cycle warning captures this broader hazard.

5. Precedent Exists — Cigarette, Lead Paint, and Food Warnings

Public health history shows that label warnings work. Cigarette warnings didn’t ban smoking — they informed choice and drove gradual change. Similarly, food and toy safety warnings helped eliminate lead and unsafe additives. A simple, visible label on school-use plastic tiffins can do the same — encourage safer markets without banning products outright.

6. A Proactive, Low-Cost Policy Tool

Unlike bans or product recalls, a warning label is inexpensive and non-disruptive. It empowers parents and schools, creates market demand for safer alternatives, and nudges manufacturers toward safer materials. In short, it’s the most cost-effective child health protection measure available.

7. The Message Should Be Clear and Caring

Concluding Words

In 2022, 175 countries came together and made a powerful promise — “Turn off the tap on plastic pollution.”

It sounds simple, but it carries a deep truth: if we don’t stop the flow of plastic, no amount of cleaning up will ever be enough.

Because here’s the thing — plastic never really disappears. They say almost every piece of plastic ever made still exists somewhere — in landfills, in our oceans, or broken down into invisible fragments called microplastics.

And those tiny bits? They don’t just stay in nature. They’re now in our food, our water, and even the air we breathe. Scientists have found them in our blood, brain, intestines, placenta — even in mother’s milk.

It’s shocking. It’s real. And it’s happening right now.

So, what can we do? We can start by turning off the tap — one small step at a time. For instance: let’s say no to plastic lunch boxes. Let’s make a simple commitment — our children’s tiffins will not be plastic.

And let’s go a step further — urging policymakers to include health warnings on plastic products, just like they do for tobacco.

Because the change we need doesn’t start in factories. It starts in our homes, in our choices, and in our everyday habits.